"That revelation should be renewed again in the latter days: God willing, is devoutly to be desired by all rational and intelligent beings." Harry Edgar Baker

Back to Faith Promoting Classics Collection |

Antelope IslandBy Solomon F. Kimball, 1909

The sun’s warm rays Beautiful isles In early days, Antelope Island was considered one of our most desirable pleasure resorts and many happy hours were spent there by our late President Brigham Young and his most intimate associates. When he visited the island, it was generally for a two-fold purpose, business and pleasure. The first white man that lived on the island, as far as our knowledge goes, was an old mountaineer who was called "Daddy" Stump. After him came Fielding Garr who had charge of the Church stock. He moved them there in 1849, and remained in charge of the animals as long as he lived. He built the old church house and corral, a part of which remains there until this day. Presidents Young and Kimball moved their horses and sheep there several years later, placing them in charge of Joseph Toronto and Peter O. Hanson. Several times they visited the island themselves. In the summer of 1856, they, in company with several of their family, spent two or three days there. The lake was quite high at the time and both Toronto and Hanson met them at the lake shore with a boat and rowed them over while the teams forded it. The time was pleasantly spent in driving over the island and in visiting places of interest: bathing, boat-riding and inspecting their horses and sheep. Old "Daddy" Stumps mountain home, then deserted, was visited. They drove their carriages as near to it as possible, and walked the remainder of the way, a distance of a half mile or more. Everything was found just as the old man had left it and a curious conglomeration of houses, barns, sheds and corrals it was. It was located at the head of a small open canyon against a steep mountain. The house was made of cedar posts set upright and covered with a dirt roof. Close to it was a good spring of water. The house and barn formed a part of the corral and just below was his orchard and garden. The peach trees were loaded with fruit no larger than walnuts. The old man, feeling that civilization was encroaching upon his rights, had picked up his duds and driven his horses and cattle to a secluded spot in Cache Valley. The last heard of him was that a Ute crept up behind him and cut his throat. The party returned to the Church ranch that evening and drove home the next day. Brother Garr died in 1855 and a year or two later Briant Stringham took charge of the stock. In 1857, quite a romantic episode took place in Salt Lake City, terminating on Antelope Island; it stirred the four hundred of Salt Lake to the center. Thos. S. Williams, then one of Salt Lake’s most prosperous merchants, closed out his business and had made extensive preparations to go East with his family where he expected to make his home. He had a beautiful and accomplished daughter engaged to David P. Kimball; but, on account of their being so young, Mr. Williams would not consent to their marriage. The young couple were determined not to be thwarted in their plans and matters became desperate with them as well as with her parents. Her father placed trusted guards over her and she was carefully watched by them night and day until the hour of departure had come. That morning, in an unguarded moment, she darted out of the back door and was out of sight almost instantly. A carriage and four horsemen were in waiting for her and before the guards had fairly missed her, she and her intended were hurled over to Judge Elias Smith’s office and were made husband and wife for all time. They then jumped into the carriage, drawn by two fiery steeds and accompanied by four mounted guards composed of Joseph A. Young, Heber P. Kimball, Quince Knowlton and Brigham Young, Jr.; they made a dash for Antelope Island, reaching their destination in less than three hours. Here the young couple spent their honeymoon, remaining there until her father was well on his journey to the East. Not a living soul knew where they were, except those who had aided them in their elopement, until they came out of their hiding place.

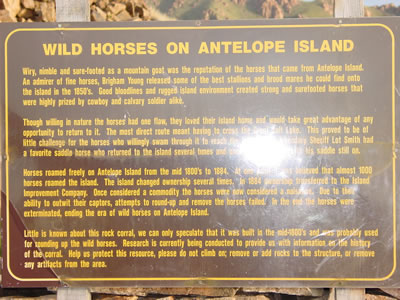

"With a small party of friends, I witnessed the launching of my boat just below the city bridge and from the west bank of the Jordan. I christened her the Timely Gull. She is forty-five feet long and designed for a stern wheel to be propelled by horses working a treadmill, and to be used mainly to transport stock between the city and Antelope Island" Every evening a couple of large campfires were made and young and old alike would unite in having a genuine good time in roasting and eating meat for the evening meal. It was amusing to see the high-toned clerks and members of the Deseret Dramatic Association sitting around these fires broiling teabone and tenderloin steaks which they had fastened to the ends of long sharp sticks. Then with bread and butter in one hand and their meat in the other, with plenty of good milk on the side, they ate their suppers with a relish that would have made the kings and noble men of the earth look on with envy. Another important feature connected with this pleasure trip that made all who were not acquainted with western life look on with amazement was the display of horsemanship. There were upwards of one thousand horses on the island, the majority of them being almost as wild as deer. Briant Stringham, who was in charge, made it a point to corral every horse on the island at least once a year. At such times, they were branded, handled and looked after in a general way. President Young had invited some of the most noted horsemen in the territory to be present on this particular occasion. They came there mounted on the best of horses to take part in the yearly round up, and they were all ready and anxious for the fray. Among them were such men as Lot Smith, Judson Stoddard, Brigham Young, Jr., Len Rice, Stephen Taylor, Ezra Clark, Heber P. Kimball, and the Ashby and Garr boys, and others, every one of whom knew the island from A to izzard. There was not one of them but could ride a bucking horse bareback or lariat the wildest mustang on the range. President Young was not long in giving them the word to go, and there was "something doing" for the next three days. The boys left the ranch early that morning in bunches of three, and about two hours apart. They crossed the island to the west side and rode leisurely along until they reached the north end, scaring up wild bands of horses as they went and heading them that way. By that time their horses were pretty well "gaunted" and ready for the 15- mile dash that lay before them. They were island-raised, long-winded, swift-footed, and their speed on a long run was something wonderful. They had been picked from the best on the island, and their worth could only be estimated by the class of men who owned them. The moment one of these wild bands were started up, they must be kept on the run until they reached their destination or they would scatter and run in every direction. No set of men could corral one of these bands unless they were expert horsemen and acquainted with all the surroundings and conditions and mounted on the best of horses. About ten o’clock on the morning of the round-up, a dust was seen near the north end of the island. It had the appearance of a whirlwind moving southward at the rate of about twenty-five miles an hour. Nothing could be seen but dust until it had reached within about two miles of the house. T. B. H. Stenhouse, and other journalists had climbed to the top of the house in order to get a full view of the approaching band. Everybody was on tiptoe, and the excitement was intense. Here they came, the speediest animals in the lead, and all of them white with foam, panting like lizards. There were about seventy-five of them in all, and some of them as fine animals as could be found in any country on earth. Those present from the old countries who had never witnessed such a scene before, stood almost paralyzed with excitement. The enthusiasm manifested by the onlookers was so great that it almost lifted them from their feet. Before they had fairly gotten their breath and recovered from the shock, another exhibition of horsemanship presented itself before them which almost left the first one in the shade. Four of the largest horsemen of them all, led by Lot Smith and Judson Stoddard, mounted four large and beautiful island horses and entered the corral where the wild horses stood snorting like so many elk. Lot led the chase with his partner close behind him, followed by Judson Stoddard and his partner. While these wild animals were on the run around the large corral, Lot threw his lariat over the front foot of one of them, while at the same moment his partner had lassoed the same animal around the neck and, with their lariats around the horns of their saddles, had in less than a half minute thrown the horse and dragged it over the soft and smooth surface of the corral (a distance of several rods) to a place where the fire and branding irons were, and in another half minute the horse was branded and turned loose. They had no more than gotten out of the way before Judson Stoddard and his partner had another horse ready for the finishing touch, and so it continued until the band had been disposed of and turned loose on the range to make room for the next one that was expected at any moment. The valuable saddle horses ridden by these expert horsemen were selected from the wild bands while on some of these long runs. It was a test that tried the mettle of every horse in the band; the horses that came out in the lead on a fifteen or twenty mile run could be depended upon as horses that were almost priceless for saddle animals over a rough and mountainous country. That day the price of island horses rose fifty per cent, and the man who could afford to own one of these beautiful animals was considered lucky. On the morning of the fourth day, President Young and party returned home, and those who composed the company declared without hesitation that they had had "the time of their lives" and would always look back to this excursion to Antelope Island with the greatest of pleasure. Antelope Island is about eighteen miles in length, and from four to six miles in width. The east side is comparatively smooth and a good wagon road extends almost its entire length. On the west side, there are many beautiful little glens, coves, and precipitous canyons, and the land is rough and rugged from one end to the other. The wild horses that once roamed over it possessed characteristics peculiar to themselves, and in many ways seemed to be as intelligent as human beings. There were two reasons for this. In the first place, they came from good stock. The "Mormon" Church, under the direction of Fielding Garr and Briant Stringham, invested thousands of dollars in valuable stallions and brood mares which were turned loose on the island. In the second place, they became nimble, wiry, and sure-footed by continually traveling over the rough trails of the island from the time they were foaled until they were grown. It became second nature to them to climb over the rugged mountain sides and to jump up and down precipitous places four or five feet high. The speed which they could make while traveling over such places was simply marvelous. They neither stumbled nor fell, no matter how rough the country nor how fast they went. They were naturally of a kind disposition and as gentle as lambs after having been handled a few times. But with all of their perfections, they had a weakness that made many a man’s face turn red with anger; they loved their island home and it was hard to wean them from it. When a favorable opportunity presented itself during the summer months, they would take the nearest cut to the island, swimming the lake wherever they happened to come to it, and keep going until they reached their destination. Lot Smith’s favorite saddle horse played this trick on him several times, even taking the saddle with him on one occasion. One of the most beautiful little nooks on the island is on the top of the mountains, about five miles from the north end. It covers nearly one square mile of ground and slopes to the west. It is made up of low hills and shallow hollows, dotted here and there with cedar and other evergreen trees. A half mile below is a small pool of living water, the only place within five miles where one can get a good drink. This was the home of the wildest horses. In 1870, an antelope was seen galloping over the hills with a band of wild horses. It was probably the only one left to represent its once numerous kind. In early days, when numerous, they learned to regard the horse as their best friend. During hard winters, when the grass was deeply covered with snow, the horses out of necessity pawed the snow off the grass and ate the best of it, then moved along to pastures new. The half-starved antelope followed closely on their heels to gather the crumbs that fell from the proverbial "table." The antelope’s appreciation of this generous act was not soon forgotten so during the summer months, when times were good and they were feeling the benefit of the rich bunch grass that had taken effect upon their lean ribs, they felt honored to have the privilege of romping over the island with their highly esteemed friends and benefactors. On one occasion, in the early fifties, when Heber P. Kimball and companions were corralling one of these wild bands, a herd of antelope ran along with them almost to the house. Hebe, touching the flanks of his horse with his spurs, darted out towards them and lariated the fattest one in the bunch, the others then scampering off to the foothills. Briant Stringham died in 1871 and, sad to say, after that there was no interest taken in the island horse. There were then about five hundred and they were allowed to run wild. For four years they never saw a human being. The Church people were anxious to get them off, and, in 1875, contracted with Chambers, White & Company, agreeing to let them have one-half of all they could deliver in Salt Lake City. These parties employed four horsemen to assist them. They shipped their outfit over to the island and began work at once. Near the north end, on the east side, they built a corral close to the lake. Ten tons of hay were stacked in the center. They built a fence from the corral to a little steep bluff, a half mile away. This formed a wing on the south side, and the lake formed one on the north. They were then ready for business. Stationing their hired men along the north end of the island to prevent the wild horses crossing to the east side, the three contractors rode south in search of horses. They had not gone far when they discovered between sixty and seventy head grazing on a low side-hill. Keeping out of sight until they came close in behind, the horses, a signal was given and a rush made towards them. The wild animals started in the right direction and everything seemed to work like a charm. One of the contractors, an old stage-driver dressed in white, who had never chased wild horses over a rough country before, got his eyes fastened upon several beautiful animals which he thought would make good stagers. With his hat in one hand and his bridle reins in the other, he went tearing down the hill, as if the "Old Nick" himself was after him. He followed a narrow trail through sagebrush as high as his horse’s back and soon came to a place where the trail forked. He took the right hand fork and his horse took the left. He went sailing over the high sagebrush like a seagull in a whirlwind. His saddle horse was found several days later, and the old man was ready for another run by that time. Everybody took a hand in the chase, as it meant several thousand dollars provided this band could be corralled. The men were all excited; discipline and pre-arrangements were thrown to the wind. The wild horses were almost frightened to death and were in the lead at least half a mile. They ran into the corral, around the haystack, and out of the gate. Every last one of them got away. This was a sad disappointment, and far-reaching since an island horse was never known to be caught in the same trap twice. It seemed like all the other horses on the island had been let into the secret, for the next day they could not find one within ten miles of there. Mr. Chambers and his companion rode around the island to scare them back, but had a hard time to find the blind trails that led north on the west side. The country for miles around seemed to be made up of large and small boulders cropping out of the ground for one to ten inches which made it almost impossible for valley-raised horses to travel. There was one place where they had to jump their horses up a steep cliff almost four feet high. They had to lead them for miles because the country was so exceedingly rough. Their horses went stumbling along as if foundered. Subsequently, they rode around the island almost every day for two months and became acquainted with every nook and corner. They visited old "Daddy" Stumps’ home several times and found nothing left but the old cabin. Inside was a prospector’s outfit with several weeks’ provisions on hand, but no sign of any person. When Mr. Chambers and companion were hunting for wild horses, the horses generally discovered them first, as they appeared to have their sentinels out in time of danger, while their scent was as keen as a bloodhound’s which gave them a double advantage. When they saw one coming, the old stallion—the leader of the band—would hide his family of horses behind a clump of cedars or in some other convenient place. He would then get back of a high rock and stand upon his hind legs, resting his front feet upon the rock, peeping over so that he showed no part of his body but the top of his head. Many times they were seen doing this as well as other tricks of a similar nature. They then watched the movements of their pursuers and when these got disagreeably close, the horses gave the alarm and away the animals would go single file over the rough mountain trails at the rate of ten miles an hour. Another trick the horses often played was this: When they saw one coming towards them, they would run at full speed over the nearest ridge and, just before going out of sight, would turn sharply to the right or left. Then, when well out of sight, would wheel around and run in the opposite direction. Their followers, at breakneck speed, would cut across the country to head them off; but when they reached the top of the ridge they would discover that the horses had gone the other way and were out of sight. They kept a person guessing all the time and none could tell what trick they would spring next. Near the north end of the island to the west side is a little mountain that projects out into the lake. By following the lake shore, it was about four miles from this mountain to the corral. After the horses had been driven from the south end of the island, they generally took refuge behind this little mountain. The men ran them through the deep sand the whole distance around to the corral, and in this way captured nearly one hundred head. One day the men got about ninety wild horses behind this mountain but, unfortunately, some of them were the same that had been corralled before but had gotten away. After they had been run through the sand to the extreme north end of the island, rather than be corralled, they lunged into the lake and swam to the promontory some fifteen or twenty miles away. Among the first horses caught were some of the largest and best on the island. During the month of May there came a severe snowstorm, and eighteen of the most valuable of these chilled and died. The balance were shipped to Layton and placed in a pasture where they remained until the men had completed their work. Several of the island horses were used as saddle animals to take the place of the clumsy valley horse which was not fit for riding over rough country.

Here the men spent a week in building a stone corral. They walled up the lower trail at the south end to prevent the horses from going that way. While this work was going on, they often saw wild horses looking over the tops of high rocks at them. When their work was completed, they rode back to camp with a good deal of joy and satisfaction, feeling they had at last outwitted the cunning and crafty island horse. They rode slowly along until they reached within a few hundred feet of the rock enclosure when, with a rush and whoop, they ran their horses to the entrance. But lo and behold, all they discovered was a large horse track. A horse had deliberately walked into the corral, all around it, and then out again, and was gone! It seemed as if he had been sent there to inspect the work and report to the proper horse authorities, and that the news had been sent broadcast over the island warning every horse of the cunning trap laid for them. Suffice it to say, every horse that had been driven around the south end of the island that day had crossed to the east side over a secret pass which only the horses knew. The men were dumbfounded and disgusted with themselves and everything connected with Antelope Island. They rode back to camp with drooped heads and not one of them uttered word or batted an eye. They got their outfit together and the next day were in Layton "necking" island horses and getting them ready for the final drive to Salt Lake City. To cap the climax, sixteen head of their best horses lifted their heads and tails skyward and with several snorts made a bee-line for the Sand Ridge. They went over fences, ditches, chicken coops and everything in front of them. Single file, they followed the railroad track until they came to the railroad bridge over Kay’s Creek. It was about one hundred feet across with sharp-edged ties at both ends. They planted their feet squarely upon these ties better than a man could have done and trotted right over. Not one of them stumbled or made a misstep. A farmer’s horse in the field close by became excited and undertook to follow them, but the first step he took on the sharp-edged ties, he went head over heels and almost broke his neck. After the horses had reached the Sand Ridge northwest of Layton, all the horsemen in Davis county could not have brought them back. The people of Kaysville stocked the island with ten thousand head of sheep. Feed became scarce, and many horses died of starvation. Adam Patterson, in 1877, purchased ten thousand acres of railroad land on the island and the sheep were moved off that year. The Island Improvement Company obtained possession of the island in 1884, and there were about one hundred wild horses left. They had become a nuisance, and Mr. John H. White and others went there with their long-range guns and exterminated them. Thus ended the horses of Antelope Island—once the pride of such men as Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball and hundreds of others who knew the value of a good horse.

|

How grand to be

How grand to be It was about the year 1860 that President Young, at the head of a select party of prominent men, visited Antelope Island again. He took all of his clerks with him, the majority of whom were good musicians. They formed a splendid string band, led by Horace K. Whitney, and many pleasant hours were spent in listening to their sweet music. The party remained there three days enjoying a continued feast of pleasure the whole time. Much of the time was spent in boating, bathing and climbing to the topmost peaks of the island. All places of interest were visited, some riding in carriages, others on horseback, and some going afoot. Many visited the wreck of the once famous boat, "Timely Gull." The heavy winds from the southeast had broken it loose from its moorings at Black Rock, two years before, and had driven it to the south end of the island and thrown it high and dry upon the rocky beach. This was the first boat of consequence that was ever sailed upon the waters of the Salt Lake. When the boat was first launched, President Young, with a select party, made several excursions over the lake with it, and it was considered to be quite a novelty in those days. The following is taken from President Young’s journal of January 30, 1854:

It was about the year 1860 that President Young, at the head of a select party of prominent men, visited Antelope Island again. He took all of his clerks with him, the majority of whom were good musicians. They formed a splendid string band, led by Horace K. Whitney, and many pleasant hours were spent in listening to their sweet music. The party remained there three days enjoying a continued feast of pleasure the whole time. Much of the time was spent in boating, bathing and climbing to the topmost peaks of the island. All places of interest were visited, some riding in carriages, others on horseback, and some going afoot. Many visited the wreck of the once famous boat, "Timely Gull." The heavy winds from the southeast had broken it loose from its moorings at Black Rock, two years before, and had driven it to the south end of the island and thrown it high and dry upon the rocky beach. This was the first boat of consequence that was ever sailed upon the waters of the Salt Lake. When the boat was first launched, President Young, with a select party, made several excursions over the lake with it, and it was considered to be quite a novelty in those days. The following is taken from President Young’s journal of January 30, 1854: By the middle of June, the horses on the island were as fat and sleek as seals and the large bands were broken up into small ones. The men worked faithfully for ten days, but never corralled a horse, and were almost discouraged. They finally adopted a new plan. There was a place on the west side where two trails paralleled each other for a mile. Apparently, there was no way of crossing the island for several miles south of this point. Neither was there any way of getting around these trails or going from one to the other. At the north end of the upper one was a natural gate formed by two large rocks.

By the middle of June, the horses on the island were as fat and sleek as seals and the large bands were broken up into small ones. The men worked faithfully for ten days, but never corralled a horse, and were almost discouraged. They finally adopted a new plan. There was a place on the west side where two trails paralleled each other for a mile. Apparently, there was no way of crossing the island for several miles south of this point. Neither was there any way of getting around these trails or going from one to the other. At the north end of the upper one was a natural gate formed by two large rocks. Bright and early the next morning they rode south, on the east side, scaring up wild bands as they went and heading them in that direction They also went around the south end, at the same time taking precautions to prevent the horses from crossing back to the east side. They then rode northward, visiting every nook and corner, and making a clean sweep. There was a good deal of enthusiasm among them, and excitement was at a high pitch. Their expectations were so great that they could hardly contain themselves. The majority were afraid that the corral would be too small, as they expected to capture almost every horse on the island that day.

Bright and early the next morning they rode south, on the east side, scaring up wild bands as they went and heading them in that direction They also went around the south end, at the same time taking precautions to prevent the horses from crossing back to the east side. They then rode northward, visiting every nook and corner, and making a clean sweep. There was a good deal of enthusiasm among them, and excitement was at a high pitch. Their expectations were so great that they could hardly contain themselves. The majority were afraid that the corral would be too small, as they expected to capture almost every horse on the island that day.

The old Church house, built by Fielding Garr, in 1849, still remains in good condition. Mr. Scott Gamble, who has charge of the company’s interests, lives there now. There are twenty-four hundred acres of land fenced in, and one thousand acres under cultivation. Fifty head of buffalo and six hundred head of Hereford cattle now roam over the island. Mr. John H. White, who has had more to do with Antelope Island since the days of Brigham Young than any other man, thinks that the day is not far distant when the west side of the island will become one of the most noted pleasure resorts in the world.

The old Church house, built by Fielding Garr, in 1849, still remains in good condition. Mr. Scott Gamble, who has charge of the company’s interests, lives there now. There are twenty-four hundred acres of land fenced in, and one thousand acres under cultivation. Fifty head of buffalo and six hundred head of Hereford cattle now roam over the island. Mr. John H. White, who has had more to do with Antelope Island since the days of Brigham Young than any other man, thinks that the day is not far distant when the west side of the island will become one of the most noted pleasure resorts in the world.